Armistice Day Address Robert Lusby AM

Concord Repatriation General Hospital, 11 November 2019

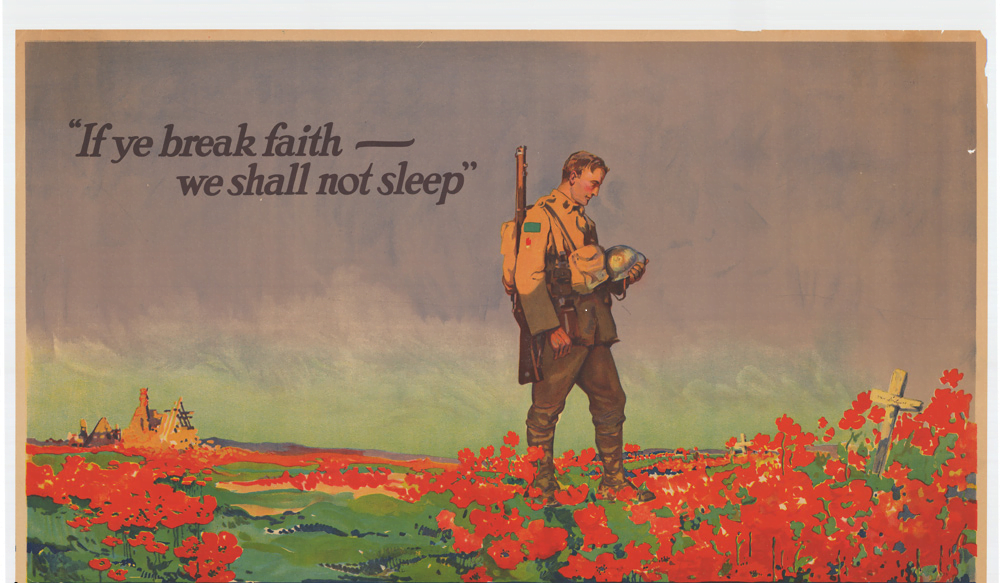

“If ye break faith with us—–we shall not sleep”

Words from the Western Front poem “In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae

Chilling words from the dead that reflect the social contract between those who have served and the families and community that released them to serve.

Those words still relevant today, when we reflect on the support of returned service men and women and their families and note the high suicide rate indicative of their plight.

Since moving to the Hunter Valley, I have been attending ANZAC memorial services in the small town of Branxton (founded in 1826). There is a rotunda where the band plays and people gather around in silence or singing well-known hymns fit for the occasion. The Last Post is played and Reveille follows the minute’s silence.

It is here that communities come to mourn the loss of men and women who have died in foreign fields and express gratitude for those who have returned.

The evocative playing of the last post at the end of Peter Sculthorpe’s composition “Small Town” is a stark reminder of the impact of the Great world war on country Australia.

Some 40% of recruits came from these towns and when they failed to return it had a devastating effect on the small communities.

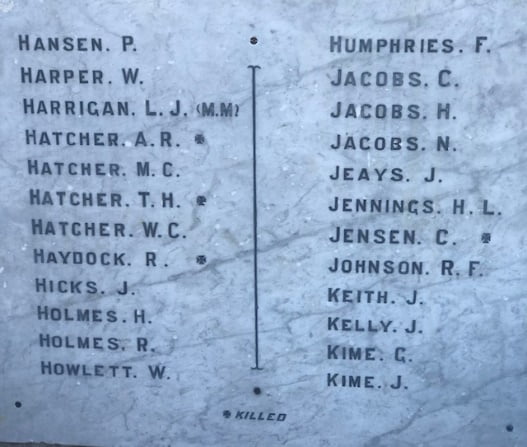

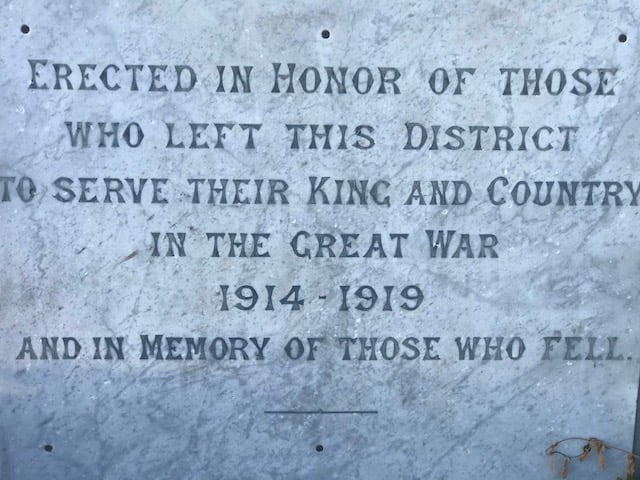

Communities all along the Hunter Valley from Newcastle to Murrinbindi, have memorials commemorating their sons who served and many died initially during the First World War and in subsequent conflicts. The same can be found across Australia.

The names of men, often multiple from the same family, reflect the tragedy of the needless Great War.

In Great Britain evidence of the shared heartbreak can be seen by the presence of a memorial cross in every village or monument in nearby towns.

Indeed, in every Cathedral of France, there is a tablet bearing the inscription “To the greater Glory of God and in memory of the one million men of the British Empire who died in the Great War and of whom the greater number rest in France”

It is often said the young men went off to war seeing it as a great adventure, one not to be missed and having caught “War Fever”.

It is not as simple as that; how could it be?

It was, indeed, with the backing of their families and friends that these men went off in defense of the Empire of which we were a part.

Why did we as a young country see it as our patriotic duty to support the “Mother Country”?

In the build-up to war, the rapid emergence of Germany as a force and cause of instability in Europe did not go unnoticed here in Australia. Furthermore, we were concerned about German Pacific involvement.

Following Federation, we took steps to enhance our security including the formation of the Royal Australian Navy.

Our understanding was clearly, that that being a Nation carries a duty to keep intact the freedoms we have inherited, including the belief in a parliamentary democracy that was the backbone of our society.

The Austro-Hungarian and German governments were very much the playthings of their ruling classes and posed a real threat.

At the time freedom and its preservation was the underlying societal justification that enabled acceptance of the enlistment of so many young men.

It is for that reason we often hear “they fought for our Freedom”.

Our Anglo-Celtic society drew on the strong and hard-won rights of individuals originating as far back as the Anglo-Saxon common law.

The Viking settlements in Britain where Dane law introduced the presumption of innocence (as opposed to Roman law which still prevails in much of Europe).

The signing of Magna Carta and the evolution of Parliamentary Democracy through to the English civil war and the so-called Glorious revolution all impacted on our culture and psyche.

Despite the convict origins of Australia, the enlightened philosophy behind that great experiment, the gold rushes, and the development of agricultural industries had all contributed to develop a new national image.

The era of the Enlightenment and the ideas of people such as Edmund Burke, the Anglo-Irish philosopher, and statesman impacted our society.

Henry Parks and the drive to Federation had a unifying influence on the people of Australia and clearly, by the start of the First World War, we were a fairly harmonious country but still a part of the British Empire.

Recently, in an address to the Concord Medical Staff, Justice Michael Kirby, a local Concord boy, recalled waving flags at Mrs. Elenore Roosevelt as she passed by to visit the new Concord Hospital. Those flags were all Union Jacks, we were part of the Empire!

In fact, Australia became a nation separate from the British Empire as late as 1942. You may recall the words of Prime Minister Menzies at the start of World War Two, “Britain has declared war on Germany and as a result, we are at war also”

Indeed, we had taken up arms to join the Imperial Forces in the fight the Bores in South Africa, at the time of Federation.

Subsequently, the Australian government recognized the need for the young nation to have some defense capability and introduced a form of compulsory military training in 1911 whereby all boys between 12 and 18 were trained as cadets and then served in the Citizen Military Forces till aged 25 years.

However, they could not be conscripted to serve overseas but could volunteer to join the Australian Imperial Force. This did provide a pool of young men familiar with rifle shooting and aspects of military service.

We are all aware of the divisive nature of the topic of compulsory war service and in the end, two referenda showed the majority of Australians were against conscription.

This is an important point as it demonstrates that the people rejected the will of the political class while sanctioning voluntary enlistment. Communities could release their sons to go to war on behalf of Australia, but not at the behest of the elected politicians.

At the beginning of the Great War, feelings were such that recruitment numbers were so high, men were turned away!

Of course, this didn’t last and casualty rates became a reality such that by 1916 there was a shortage of volunteers.

Dr. Neville Howes VC, Colonel in charge of medical services insisted on only fit men be taken, aged 19 to 38 and at least 5 feet 6 inches tall. The reality of tall fit young men, often good shots coming from the country with an independent spirit reflected the recruiting drive. Their valour, spirit, and stamina contributed to the ANZAC tradition.

Edmond Burke once said, ”a nation is a partnership between the people who have died, the people who are living and the people who haven’t yet been born” .

This implicit partnership underpinned the enthusiasm young men of a new nation volunteering to serve in defense of the empire that had given birth to Australia, and the acceptance by the community.

As the famous military theorist, Carl von Clausewitz defined “War, is thus an act to force or compel our enemy to do our will”. We, as a nation had the will to resist fueled by our volunteers, many of whom along with their families paid the ultimate price.

Clausewitz also noted “war is merely the continuation of politics by other means”. The failure of the political class to find a resolution, in the end, is part of the tragedy of the Great War and impacted millions of people while the underlying politics were not resolved.

The great tragedy of war is its impact on those who serve and their families – a situation that has not changed.

Our initiative at Concord Hospital, with the National Centre for Veterans Healthcare, is a belated attempt to help some of the 60,000 service personnel who are currently in our community.

The situation is complex, we don’t always see suicide coming for instance. There is a need for research alongside clinical care to further our understanding.

The many issues involved a Royal Commission is unlikely to unearth although it might highlight the situation.

A quote from Alan Moorehead’s book “Gallipoli” sums up the essence of the situation.

Xerxes, the Persian commander, bridged the gap to the north of Gallipoli with a floating bridge in preparation for his invasion of Greece –

Xerxes, the Persian commander, bridged the gap to the north of Gallipoli with a floating bridge in preparation for his invasion of Greece –

“and now, as he looked and saw the whole Hellespont covered with the vessels of his fleet and all the shore and every plain as full as possible of men Xerxes congratulated himself upon his good fortune; but after a while, he wept”.

Lest we forget

Robert Lusby AM Emeritus Professor University of Sydney,

Retired Colonel Royal Australian Army Medical Corps

Co-Chair National Centre for Veterans Healthcare.

I have used the following in preparing this address

Gallipoli, Alan Moorehead 1956 Mead & Beckett Australia

The First World War, John Keegan, 1998 Random House, London

ANZACS Australians at War, A K MacDougall 1991 Reed Books, Australia

On War, Carl von Clausewitz Anatol Rapoport translator, 1968 Viking Penguin

#aroundhermitage #huntervalley #bobsblog #tintillaestate

Author: Robert Lusby AM

©Around Hermitage Association Inc.